BAD JOKE

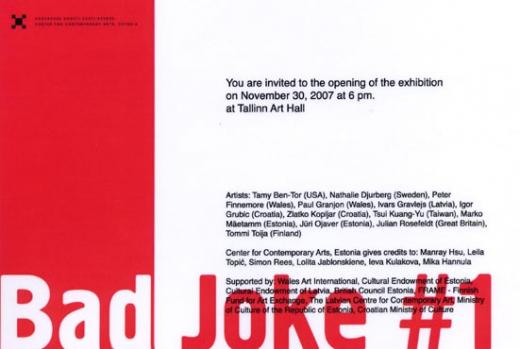

30.11.07.-06.01.08 International group exhibition ”Bad Joke # 1” in Tallinn Art Hall, curator Johannes Saar. Participants from Estonia: Marko Mäetamm, Jüri Ojaver.

PRESS RELEASE

BAD JOKE # 1

30.11.07.-06.01.08

Opening on November 30, 2007 at 6 pm. at Tallinn Art Hall

Artists: Tamy Ben-Tor (USA), Nathalie Djurberg (Sweden), Peter Finnemore (Wales), Paul Granjon (Wales), Ivars Gravlejs (Latvia), Igor Grubic (Croatia), Zlatko Kopljar (Croatia), Tsui Kuang-Yu (Taiwan), Marko Mäetamm (Estonia), Jüri Ojaver (Estonia), Julian Rosefeldt (Great Britain), Tommi Toija (Finland)

Supported by: Wales Art International, Cultural Endowment of Estonia, Cultural Endowment of Latvia, British Council Estonia, FRAME - Finnish Fund for Art Exchange, The Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Estonia, Croatian Ministry of Culture.

This exhibition has grown out of my own personal problems with adjusting to other people, often to those closest to me. In the tradition of the fundamental attribution error, as it is known in sociology, I tend to blame these problems on the unfavourable conditions. The onlookers, however, in the same unfortunate vein, usually see them as my “own fault” first of all. This controversy alone is enough to give life to images and more accurate concepts of inappropriate behaviour. Psychological, cultural and social clashes that occur with the fusion of two or more cultural areas or opinions put forward the concept of “inappropriateness” as an evaluative standard. They also propagate the theoretical concept of topos (where things are located in fundamentally the wrong places) and the manners that have no place in “our” daily life. The universal tendency of all cultural communities to reproduce the normative status quo and repeatedly put objects and people “back in their (right) place”, as described by cultural anthropologist Claude-Lévi Strauss, falls under attack and, even if only temporarily, gets lost in Priit Pärn’s Backwardshire, Gulliver’s Visions, or the semiotic chaos in Peter Bichsel’s book "America Doesn't Exist". And perhaps even in Mikhail Bakhtin's subversive social carnival.

The colonialist, patronising relationship between the great white man and the small dark-skinned aborigine is the recurrent image providing the impetus for the present post-colonial critique of racism, globalisation, social segregation and cultural ghettoisation. I would not dare to promise that “Bad Joke” in its current version at the Tallinn Art Hall and later travelling to Latvia and Croatia with a growing number of participants, weighs in with a comment on all the various clusters of problems mentioned here. But we could hope that the artists in this exhibition demonstrate some inappropriate models of behaviour that, being uneasy and odd, shed light on the strict conventions that imperceptibly control our facial expressions at funerals and exhibition openings, our notions of gender roles, expectations of electric sockets and the Orient, or that form our attitude to the talking frankfurter. Routine everyday practices under the attack of changing life forms – could there be an experience more liberating than that?

Johannes Saar

Exhibition concept:

"…no prostitute greets a new visitor with as much joy as history greets a new hero"

Leonid Andrejev, Satan’s Diary

Bad Joke #1 presents the viewer with a gallery of heroic con-artists with a strong desire to blend into society. We observe a crowd of characters jostling on the threshold of history, attempting to edge their way into the noble society of annals and chronicles. Their Don Quixote-like passion for the heroic is surpassed only by their unsuitability as pillars of society. The term "fools of fame" is possibly an honorary title with which society is willing to embrace them. In spite of their own personal endeavours and patriotism they don't succeed in dying heroically, not on the battlefield, at work or on the stage. They never become cover stories. Social re-adjustment to become Father of the Year, a searching artist, a brave soldier, a prima donna, an explorer defying great distances or a self-effacing lifesaver twists their activities out of the usual success story framework. The earnest socialiser becomes the idiotic provocateur (Ivars Gravlejs, Paul Granjon), the jam-faced goody goody turns to crime (Igor Grubic), the new generation becomes a devilish imp (Tommi Toija), the lifesaver a funeral director (Jüri Ojaver) and the father a violator (Nathalie Djurberg). Finally, the Messiah becomes the Führer (Tamy Ben-Tor).

Tsui Kuang-Yu from Taiwan, the cosmopolitan flâneur on the streets, avenues and parks of world cities; in him we meet more than one elegant cultural stereotype – Charles Baudelaire's promenading dandy, Walter Benjamin's inquisitive bourgeois and Paris' situationist drifter – all suddenly finding themselves as the main characters in a Taiwanese slapstick comedy, aimlessly colliding in a modern cityscape, battling against a rebellion of modern household appliances and taking refuge from the rain under the cover of role play.

Peter Finnemore from Wales rips the heroic aura from history, presenting its scenes in a cosy home theatre. Figures in patchy camouflage uniforms pottering in the garden, the forest and indoors. They experiment with night-vision technology, stalk among the sunflowers and organise training drills. The domestic garden becomes a training camp. But the constant preparedness for war never reaches its logical conclusion, the counterpoint is never achieved and the enemy never appears. The macho posturing is subdued to the scale of a puppet theatre, where suddenly children and ginger cats have a more important role than the Man Who Was Preparing to Save the World.

Jüri Ojaver's "lifesaver" is also based on the need to save the world. On the edge of a freshly dug grave, looking through a telescope at the drowned, he saves those for whom the sea has prepared a funeral. Ojaver’s hero suddenly discovers that he has risen, without competition, to be the best lifesaver among funeral directors. The conflict between social roles finally ruins both the funeral atmosphere and the desire to work, and as a result there is all the more room for awkwardness, bad jokes and inappropriate remarks thereby breaking society's strict contracts concerning the division of roles.

In his own way Marko Mäetamm does this too by presenting us with a text for those situations in the social theatre, which are not in the least bit funny and where behaviour is regulated by the norms of decency. With heretical pleasure he rips the entire rhetoric of tombstones out of the the rituals of mourning, adding even more over stated theatrical colour and transforming it into a personal exhibition project in a gallery – an exalted hexameter minus the loved ones and mourners.

But there are two artists who prefer a larger scale for mockumentaries of social situations. Zlatko Kopljar travels from one seat of power to the next and kneels in reverence before them. The Square of Heavenly Peace, the British Houses of Parliament, the headquarters in Brussels, the White House in Washington and many others, all are worthy of a public display of compassion from this humble itinerant monk. The gesture, which in its morality transcends rebellion and ideologies of resistance, publicly places the seat of power in the role of victim. Something that did not go unnoticed by the police guarding the "heavenly peace" who quickly removed the artist from the square. Julian Rosefeldt’s scope is also global, but instead of worshipping the facades of power he focuses on those of culture. As a backpacker driven by the mantras of Hinduism he travels away from Hollywood towards the eternal truths of the Orient, but on arrival finds Bollywood, the world’s cheapest call centre labour force and people lost between the scenes of the film industry and the trappings of global liberalism. The Orient turns out to be nothing more than a stage set, and in the midst of the odyssey the hero becomes a "fool of fame" wandering behind the stage and amidst the audience.

According to Judith Butler’s "queer theory" we can generalise that the characters in Bad Joke are frolicking with the social props, manners and costumes that accompany well-known (and also historic) heroic roles. More than that they perform in all seriousness, and worry and even tears, are not far off. But the player lacks true conviction and the endeavour ends in farce, paraphrase and a performance where habitual traits appear before us as nothing more than hollow ritual, the foundations of society as merely cardboard decorations and history as a stock yard. There is no wonder that each performer, sweating in their costume of social integrity continuously whispers to themselves "I don’t belong here, I don’t belong here".

Johannes Saar